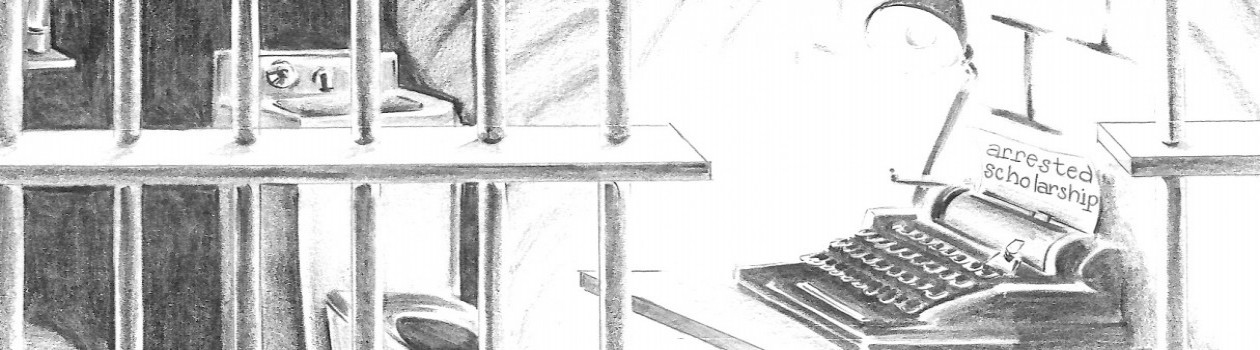

ReeRee is a slightly built, superbly athletic, and smart kid with the most infectious smile. He is nineteen years old, and does not look a day older than a 7th grader. He is from the Quad-Cities, a metropolitan area that includes towns in both Iowa and Illinois; I know the area well, I lived there, and it is where I committed crimes that have cost me the majority of my life.

ReeRee is in prison for selling drugs. After his mother died of an overdose in Milwaukee, he and his younger sister were being raised by their loving, working class, maternal grandparents. However, when his grandparents died, less than a month apart, he landed in the home of his aunt, an addict. He was fourteen and his sister was eleven months younger. They were left to fend for themselves; beyond a roof over their heads the aunt provided little else. Clothing, food, feminine hygiene products for his sister, even the utilities were left to ReeRee. He told me, “I did what I had to do for me and my sister.”

One evening last fall after ReeRee had returned to the Quad-Cities from proudly driving his sister to the east coast, and dropping her off at the Ivy League university to which she had earned a full ride, he made a costly mistake. He sold a total of $30 worth of heroin and crack to an addict who was working as an informant. He has been here ever since, but is eligible for parole next year.

Last evening as I sat trying to lose myself in a history book written by Richard Haass, ReeRee’s smiling face appeared at my door. “Hey Student,” he said–yes, I once told him that William Gossett‘s nickname was Student. “School is closed tomorrow, you gonna help me with some math?” He was referring to the school staff, where I work, being gone to a conference and leaving me with a 5-day weekend.

“Sure,” I said, “we will kick it for a couple of hours.” Then it donned on me, “ReeRee, you graduated two months ago, why do you need math help?”

He looked away, but then responded, “I am just trying to keep it in my head for the ACTs.” His voice trailed off, and he did not immediately look back towards me. I closed ‘The World: A Brief Introduction,’ placing it on my table and turning my full attention to him. Something was wrong. There has been so much gang drama and recruiting of late, I was hoping that he hadn’t fallen into that trap–one that I had worked hard to keep him away from.

“Yaa bunayya,” I said to him, what is going on, what’s wrong?” I asked.

“That’s it right there,” he said in almost a whisper. “That’s what’s wrong, you don’t tutor me anymore, so I don’t ever hear that anymore.” ReeRee is a rough and tumble little guy, but he never seems to be possessed of the need to prove his masculinity in this den of hubris–he does not hide his feelings. Yaa bunayya is the transliteration of an Arabic term which translates as “O’ my little son,” or “O’ my dear son.” ReeRee continued, “When you called me that, and told me what it meant, I loved them words. I never had a daddy. The only time I felt like I had one is sitting in that office with you learning about math, God, gangs, and girls.”

The guard came just in time to tell him to lockdown. It saved us both from the bursting dam of tears that were about to flow. I know what he is feeling, as I never had a dad either. In the morning I am going to talk God, gangs, girls, and a little math with my little son.